Provenance Revealed: Provenance research in practice

Under the title “Provenance Revealed”, we present the handling of provenance research in an exciting series of articles. In our fifth article, we report on this in daily practice at Karl & Faber Art Auctions.

What is the concrete procedure when Karl & Faber receives a work of art that was created before the end of the Second World War? If it can be proven or it is even suspected that the work of art was seized between 30 January 1933 and 8 May 1945 as a result of Nazi persecution, the art dealer is subject to a heightened duty of care.

First, the consignor is questioned – what does he know about the origin of his work? Where did he buy it or when did he inherit it and from whom? Are there any documents or expert reports on the work?

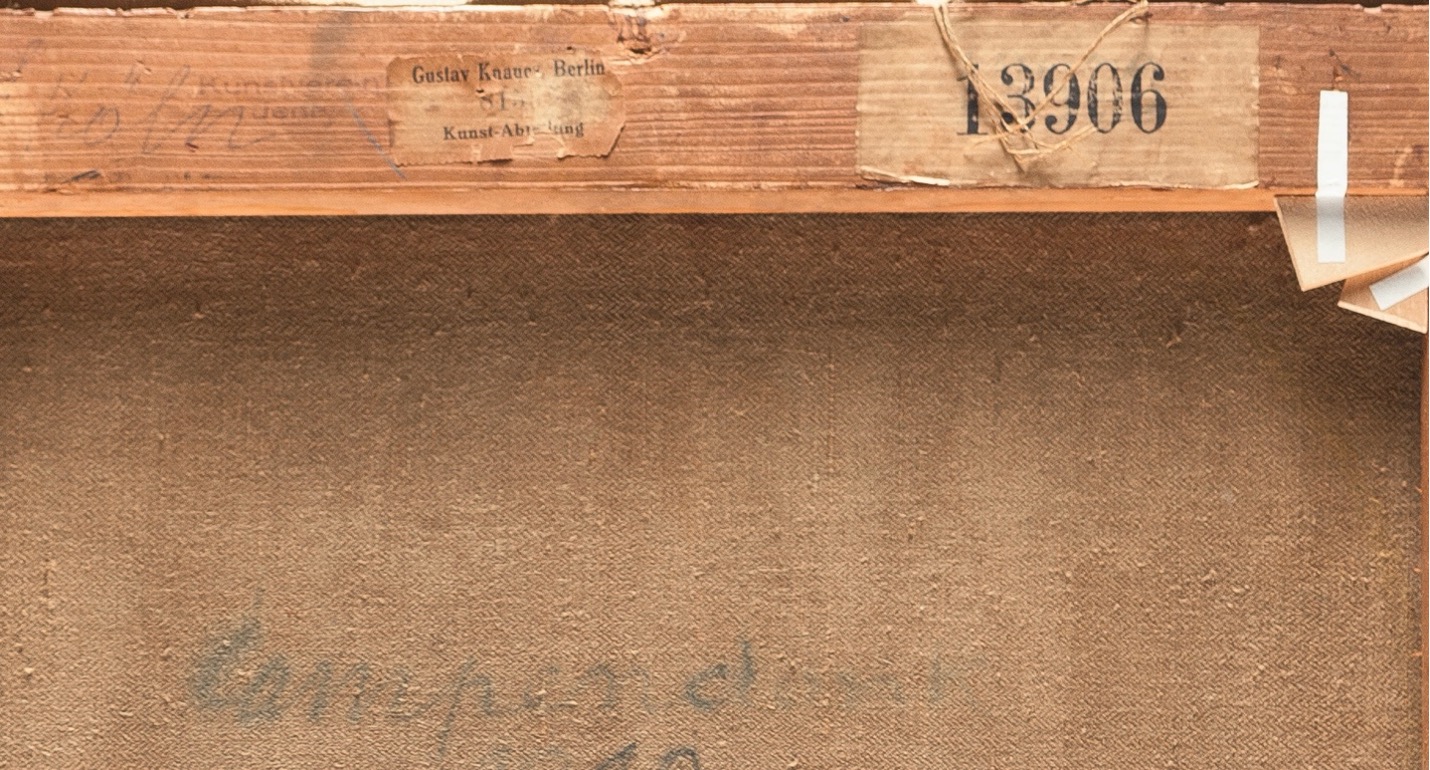

As a next step we also examine the work of art “physically”. The back of the work is particularly interesting. Are there any stamps, inscriptions or labels that could provide information about the owner, sale, transport, exhibitions or storage of the work?

Examples:

On the back of the frame of the painting “Sensuality” by Franz von Stuck we found the blue, handwritten number “17267”. This comes from the “Central Collecting Point Munich”, which was set up by the Americans in June 1945 in a former administrative building of the NSDAP at Königsplatz in Munich – this building now houses the Central Institute for Art History. You can search for these numbers in the CCP database on the website of the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin.

The complete cataloguing can be found here.

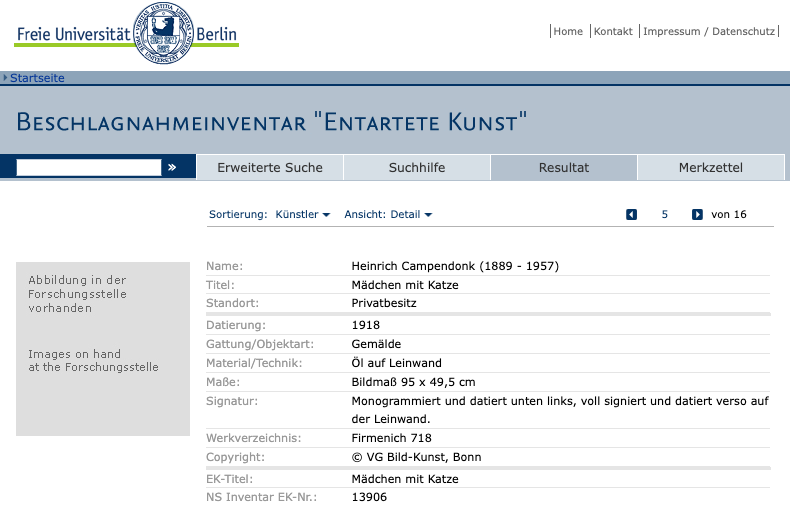

On the stretcher of the painting “Girl with Cat” by Heinrich Campendonk we discovered an adhesive label with the number “13906” – this is a so-called “EK number“ (“Entartete Kunst-Nummer“). The complete list of “degenerate art” confiscated from German museums in 1937/38 has been posted on the FU Berlin website since 2010. The label of the shipping company “Gustav Knauer” also reveals something about the history of the work: the company Gustav Knauer transported many of the 20,000 objects from German art museums that were classified as “degenerate” by the Nazi regime to the infamous exhibition “Degenerate Art” in Munich and from there to storage.

The complete catalogue can be found here.

Furthermore, we check the catalogue raisonné of the respective artist to see whether the work is listed there. Provenances and exhibitions are often indicated here, which can contain important information on the history of the artwork. If it was shown in an exhibition, the corresponding catalogue may contain references to lenders. Sometimes museums still have records of their former collections or lenders in their archives. If an auction house is mentioned in the catalogue raisonné, then we look in libraries or online for the respective auction catalogue – provenances are sometimes listed here as well. Very helpful in this respect is the website „arthistoricum.net“ with a database of “German Sales”, containing more than 12,000 digitised auction and sale catalogues from German-speaking countries from 1901 to 1945.

But how do we find out whether the names and institutions that have come up during the research have a problematic connection to the Nazi era? To do this, we research in various databases whether, for example, it is a so-called “Red Flag Name” or whether the artwork was reported as “Nazi looted property”.

The Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU), a special unit set up by the US government, produced a series of reports on Nazi cultural property looting between 1945 and 1946 – including a list of persons and entities involved, the so-called “Red Flag Names”. It contains, in particular, German art dealers who can be proven to be connected to the Nazi cultural property theft. This list still forms the basis for initial suspicions regarding Nazi looted property. The “Red Flag Names” of the ALIU can be researched in the database “Proveana”.

The database “Proveana” is linked to the database “Lost Art”, which documents works of art seized during the Nazi dictatorship. As a standard procedure, we check all works of art created before 1945 to see whether there is an entry in “Lost Art” for them. As an additional step, all works offered in our catalogues are checked against the database of the “Art-Loss-Register”.

Sophie-Antoinette von Lülsdorff