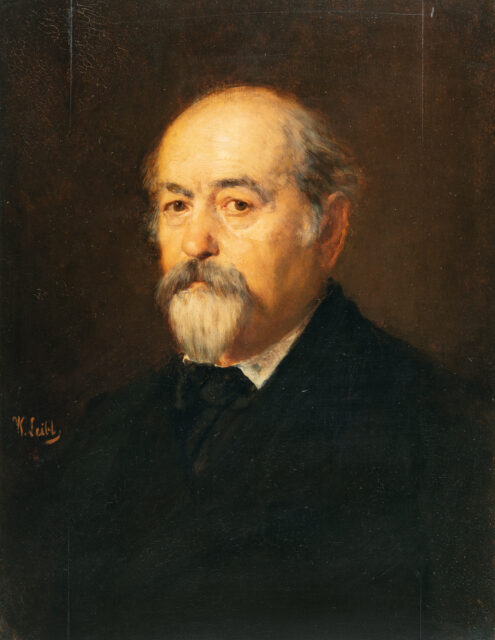

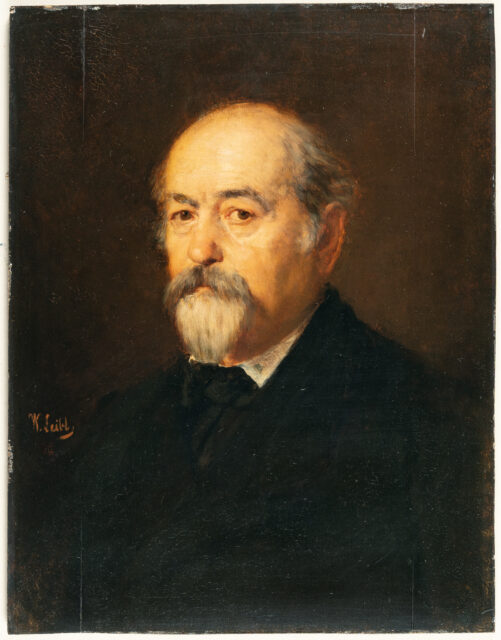

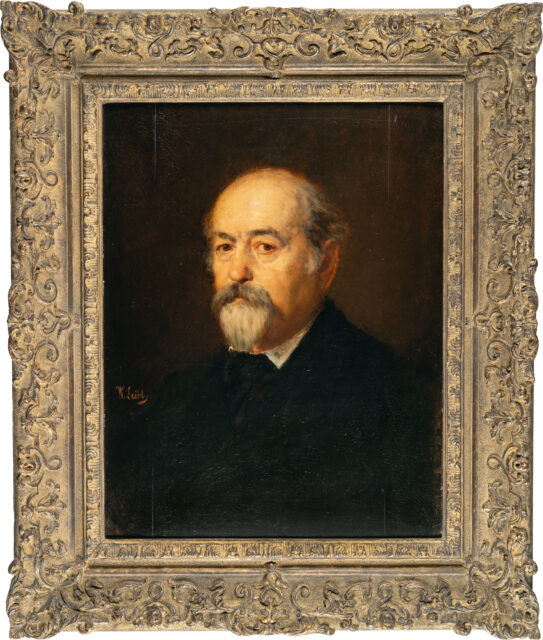

Portrait of a gentleman from Munich

Details

Waldmann 252.

Literatur:

Emil Waldmann, Wilhelm Leibl. Eine Darstellung seiner Kunst. Gesamtverzeichnis seiner Gemälde, Berlin 1914, Nachtrag, Kat.-Nr. 252, Abb. 222 (ca. 1890 datiert);

Emil Waldmann, Wilhelm Leibl. Eine Darstellung seiner Kunst. Gesamtverzeichnis seiner Gemälde, Berlin 1930, Kat.-Nr. 72 (ca. 1867 datiert).

Provenienz:

Professor Edinger, Frankfurt a.M.;

Frau Professor Edinger, Frankfurt a.M.;

Privatbesitz, Süddeutschland.

Description

“In this Leibl, the world’s greatest portrait painter of recent times, the greatest since Rembrandt,” wrote Julius Meier-Graefe in his “Entwicklungsgeschichte der modernen Kunst” (1904/1924). Even if Meier-Graefe dares to gallop through the centuries, he nevertheless makes important points.

For Leibl, as for the great Dutchman, the portrait was the central pictorial task in his work and yet he would not be labelled a “portraitist”. Portraits were not created as mass-produced social goods, but rather each individual portrait was created in extended sittings and in direct observation of the model. The highest technical standards met emotional depth without psychologising. For Leibl, the artists of the 17th century were far more exemplary in this respect than what was taught at the Academy during his time, which also explains the stylistic proximity to Rembrandt’s art.

An elderly gentleman sits calmly opposite us here. His head is turned to the left in three-quarter profile, but from the corner of his eye he is looking firmly at the viewer. As is so often the case with Leibl, nothing in the composition distracts from the depiction of the man. The composition is so tightly framed that the man can only be seen as a bust. Even the hands, which Leibl liked to include in the picture and which occasionally provide a clue to the social environment of the sitter by means of a personal object held in his hand, are not visible in this case. The name of the man depicted has not survived. The viewer’s attention is thus focussed entirely on the painting.

The background is in shades of brown, revealing nothing of the surrounding space and also suggesting little depth. The black jacket barely stands out from the background and the black tie in the lapel neckline can only be guessed at. Only the collar tips of the white shirt are clearly outlined and give the face an accentuated frame towards the bottom. The white corresponds with the white-grey hair on the beard and temples, which, together with the half bald head, reveal the sitter’s advanced age, as do the slightly wrinkled bags under the eyes and slightly drooping eyelids. At the same time, however, the gaze is so focussed and the nuanced incarnation so full of life that it is clear how much the subject is in the midst of life. In particular, the brightly lit, high forehead, which is barely criss-crossed by wrinkles and certainly not by worry lines, indicates an alert, self-assured spirit. His gaze is scrutinising, without revealing the judgement of this critical observer from the rest of his facial expressions. And yet there is a hint of melancholy in his features, paired with benevolent sympathy.

Stylistically, the portrait can be dated to around 1867, when various artists began to gather around Leibl, who would soon form the so-called Leibl circle with its own concept of realism. The eyes are modelled with fine brushstrokes and individual beard and head hairs are added, while the majority of the incarnation, hair and clothing are applied with coarser brushstrokes. Fully committed to the idea of the “pure painting” of the Leibl circle, the artistic “how” takes precedence over the narrative “what” of the pictorial object, which, whether with fine or coarse brushstrokes, is not formed from the line but entirely from the colour.

Regarding the provenance: Emil Waldmann gave “Professor Edinger, Frankfurt a.M.” as the provenance in 1914 and “Frau Professor Edinger, Frankfurt a.M.” in 1930. This probably refers to the renowned neurologist and founder of the Neurological Institute at Frankfurt University Ludwig Edinger (1855-1918) and his wife Anna (1863-1929). Anna came from the wealthy, art-loving Frankfurt banking family Goldschmidt and was able to enable her husband to conduct independent research and become the father of neurology in Germany. She herself was committed to charitable causes and was active beyond the borders of Frankfurt as a women’s rights activist.

Dr Marianne von Manstein

* All results incl. buyer’s premium (27%) without VAT. No guarantee, subject to error.

** All post-auction prices excl. buyer's premium and VAT. No guarantee, subject to error.

*** Conditional Sale: The bid was accepted below the limit. Acquisition of the work may still be possible in our post-auction sale.

R = regular taxation

N = differential taxation on works of art which originate from a country outside of the EU

The private or commercial use of images shown on this Website, in particular through duplication or dissemination, is not permitted. All rights reserved.